The Genius Design of the Book

The Permanence of the Codex

“Design is not just what it looks like and feels like.

Design is how it works.”

—Steve Jobs

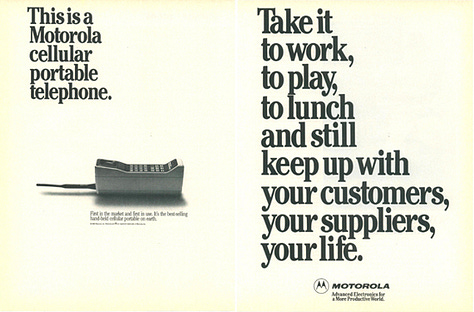

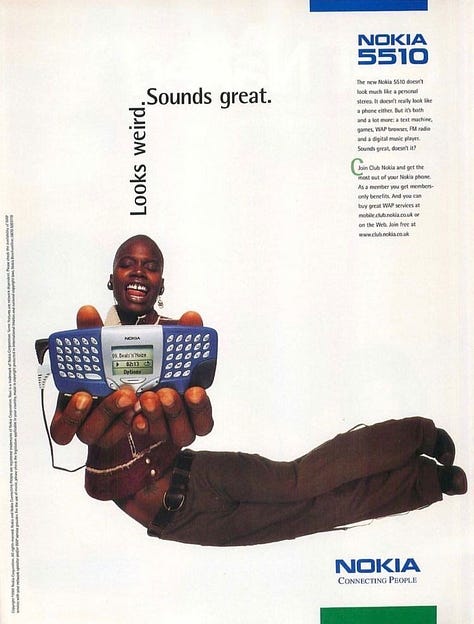

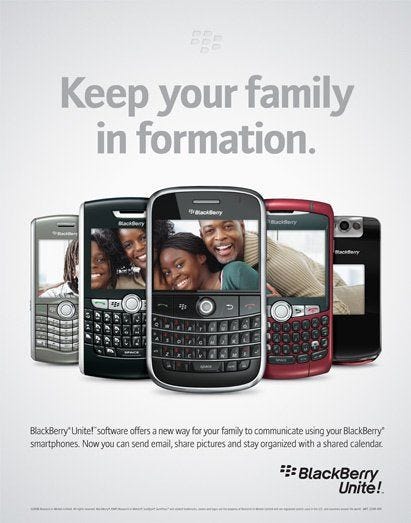

Apple’s annual September iPhone event opened up with this very apt quote this past Tuesday. For the past decade, Apple and other smartphone companies seek to define—or redefine?—the experience of the smartphone. The promise of technology is to keep progressing forward, making it better and better and better. There’s very little rest for our techy friends, there’s always something to change or improve upon. An iPhone is considered “obsolete” by Apple after it’s been off shelves for a mere seven years.

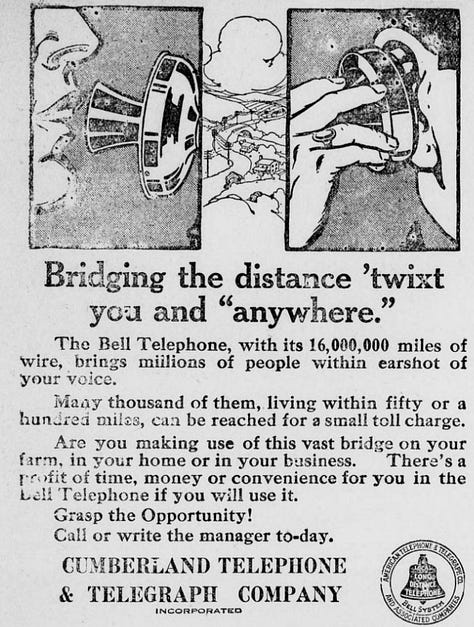

Ever since the patent for the first telephone was issued to Alexander Graham Bell in 1876, it’s been an ever evolving object with the same basic function of connecting people together across vast distances. The telephone has manifested in a vast number of forms and experiences. A reminder of how early we still are in this object’s history.

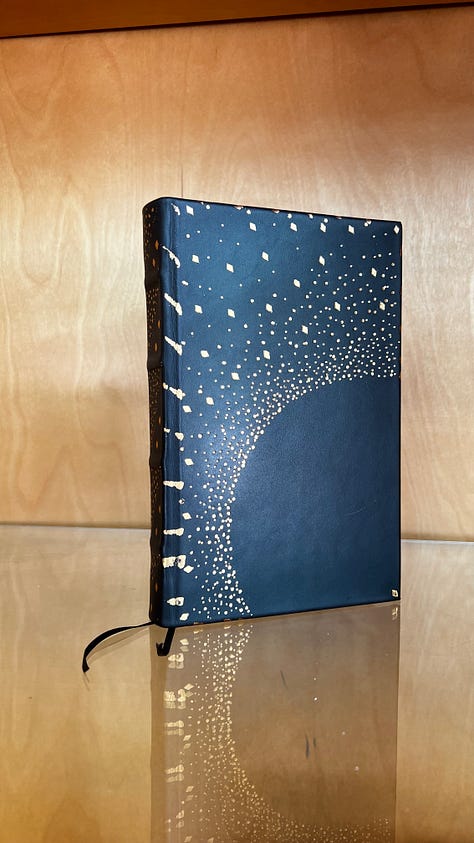

You may be asking yourself, “That’s great, what does this have to do with books?” Not much, I supposed, but watching the Apple Event reminded me of the brilliance of the book. Not the book cover, not the interior, not the literature contained therein, but the form of the book itself—otherwise known as the codex. A cool name for a cool object.

The Unchanging Codex

As Steve Jobs observed, “It’s not just what it looks like, but what it feels like.” I’m going to take that literally. The codex is a book form that is about 2,000 years old. For comparison, the telephone will reach that age in the year 3901.

Oh, and the cool part—the codex has remained largely unchanged for that span of time. Can you imagine using an iPhone 17 Pro in the year 3901?

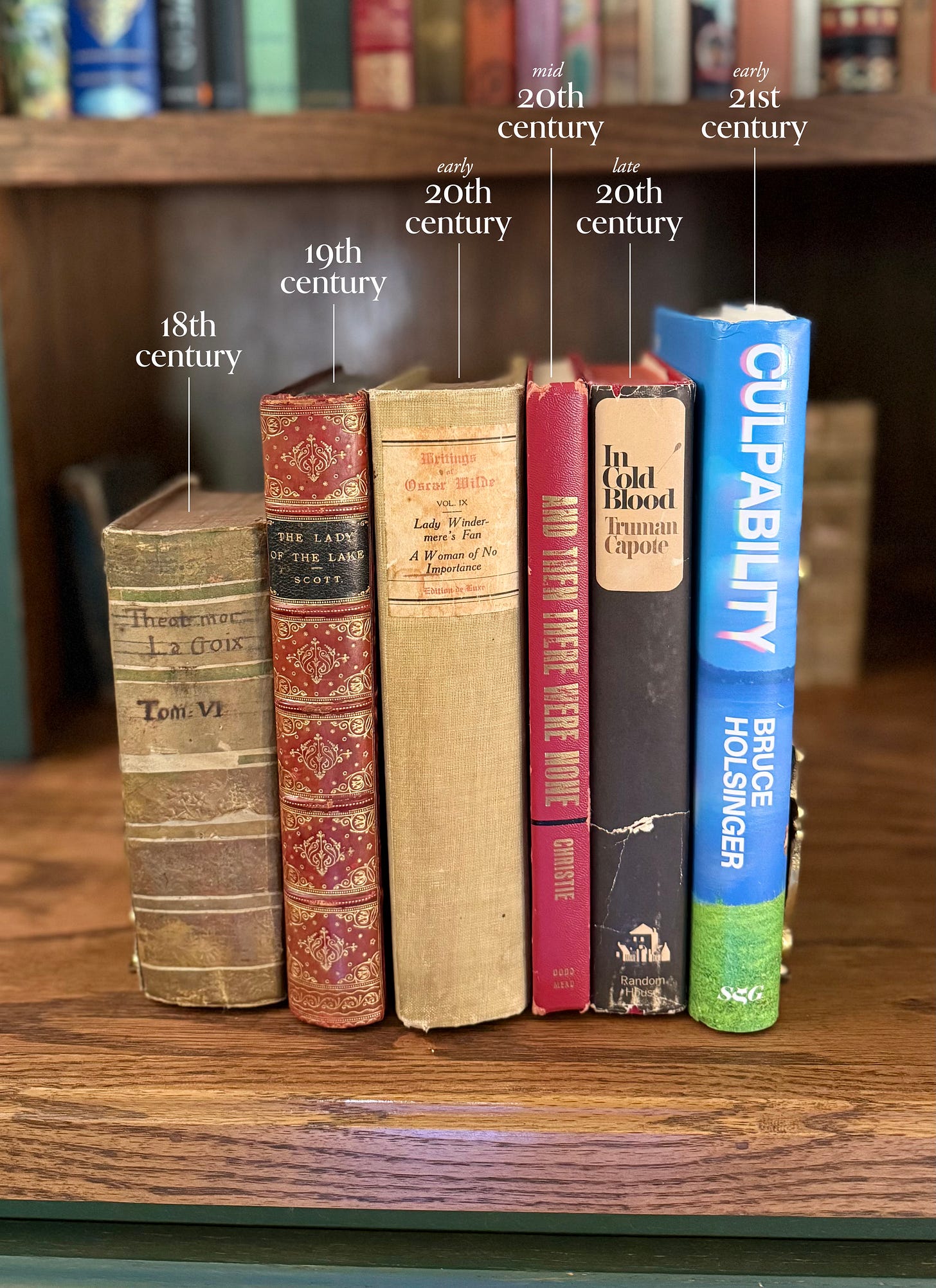

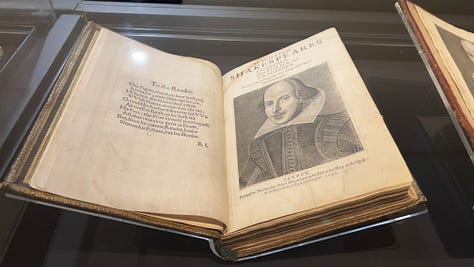

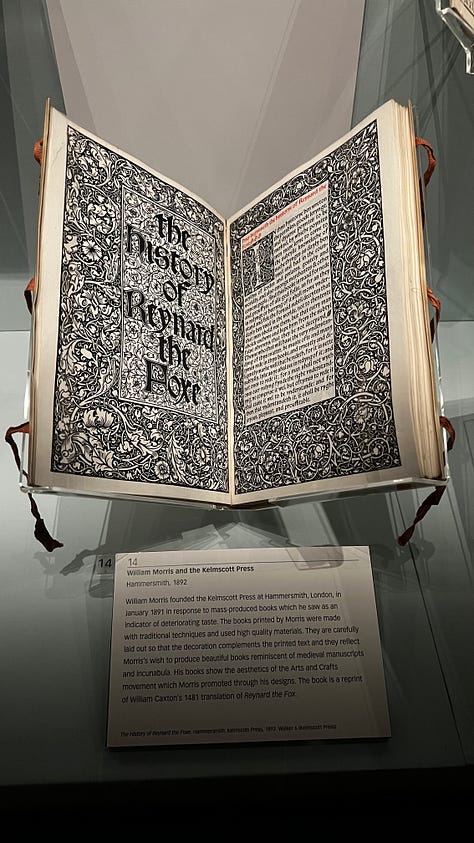

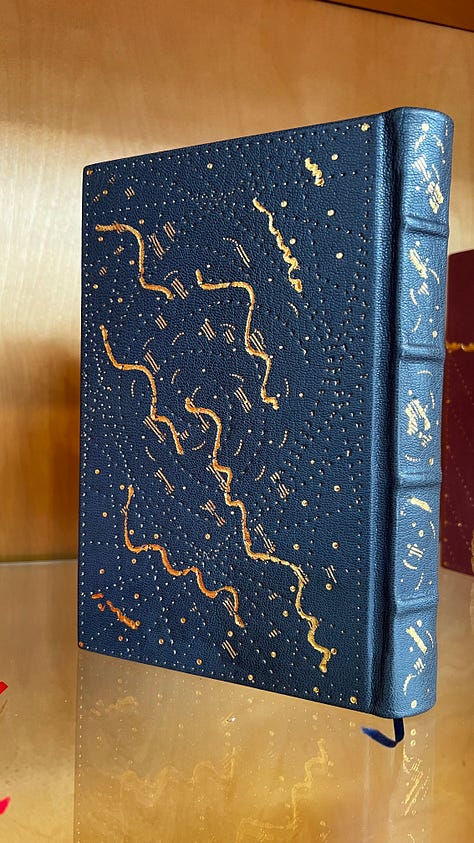

How these codices look has certainly changed over the years, but the design of the form—a series of pages (or folios) bound together between two covers—has stayed consistent. I may be biased, but I would consider it an example of perfect design.

Necessity is the Mother of Invention

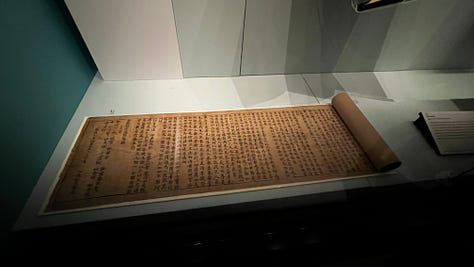

The popularity of the codex book format came about during the rise of Christianity in the 1st century AD. Christianity was a burgeoning underground religion following the teachings of Jesus Christ. Part of this subversive movement was the spreading of this message—known to Christians the Great Commission. Holy Scriptures, like any religion, became a core part of Christianity, specifically the four Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John). The codex format allowed for the merging of multiple books into a compact format making it more portable. Writing on both sides of the paper—as opposed to a single side like on papyrus—made it more economical. Navigating through the book was large improvement. Instead of having to unroll a massive scroll, it became much easier for readers to find what chapter or page they were looking for.1

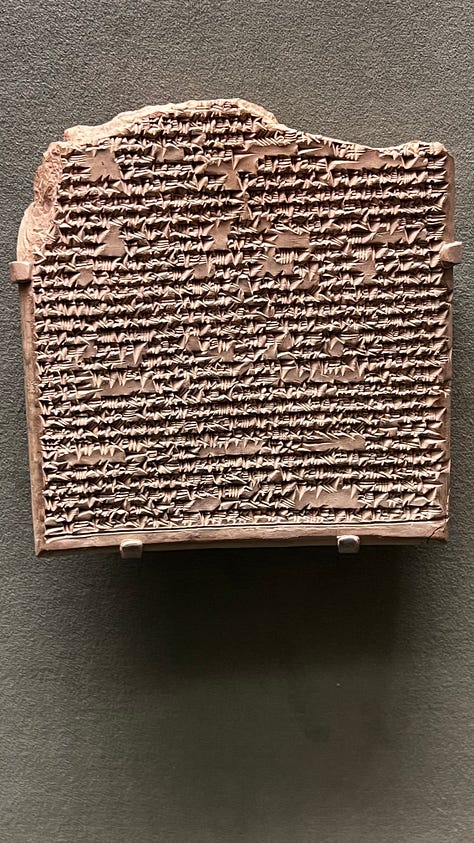

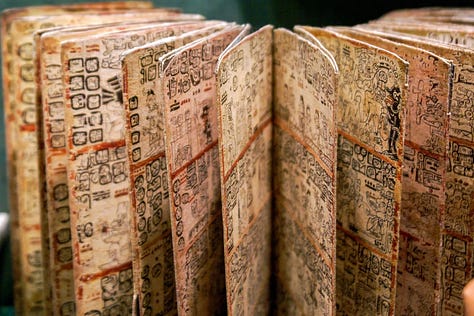

Prior to the codex, tablets, scrolls, and concertina books were the primary forms for written literature. In Greece and the Middle East, the region of the codex, papyrus scrolls were the predominant form of written communication and literature. In the transition from scroll to codex, papyrus would initially be used until the switch to parchment. This would be one of three major evolutions of the codex in its history—the other two being the transition from parchment to paper and the introduction of printing.

“The material on which the immortality of human beings depends.”

—Pliny the Elder

An Eternal Legacy

The codex today is synonymous with the book. The two are so intertwined that many people don’t know that a book takes many forms, some touched on above like the scroll and concertina. Book artists and some authors will experiment with these varying forms, and I’d like to talk about them more someday.

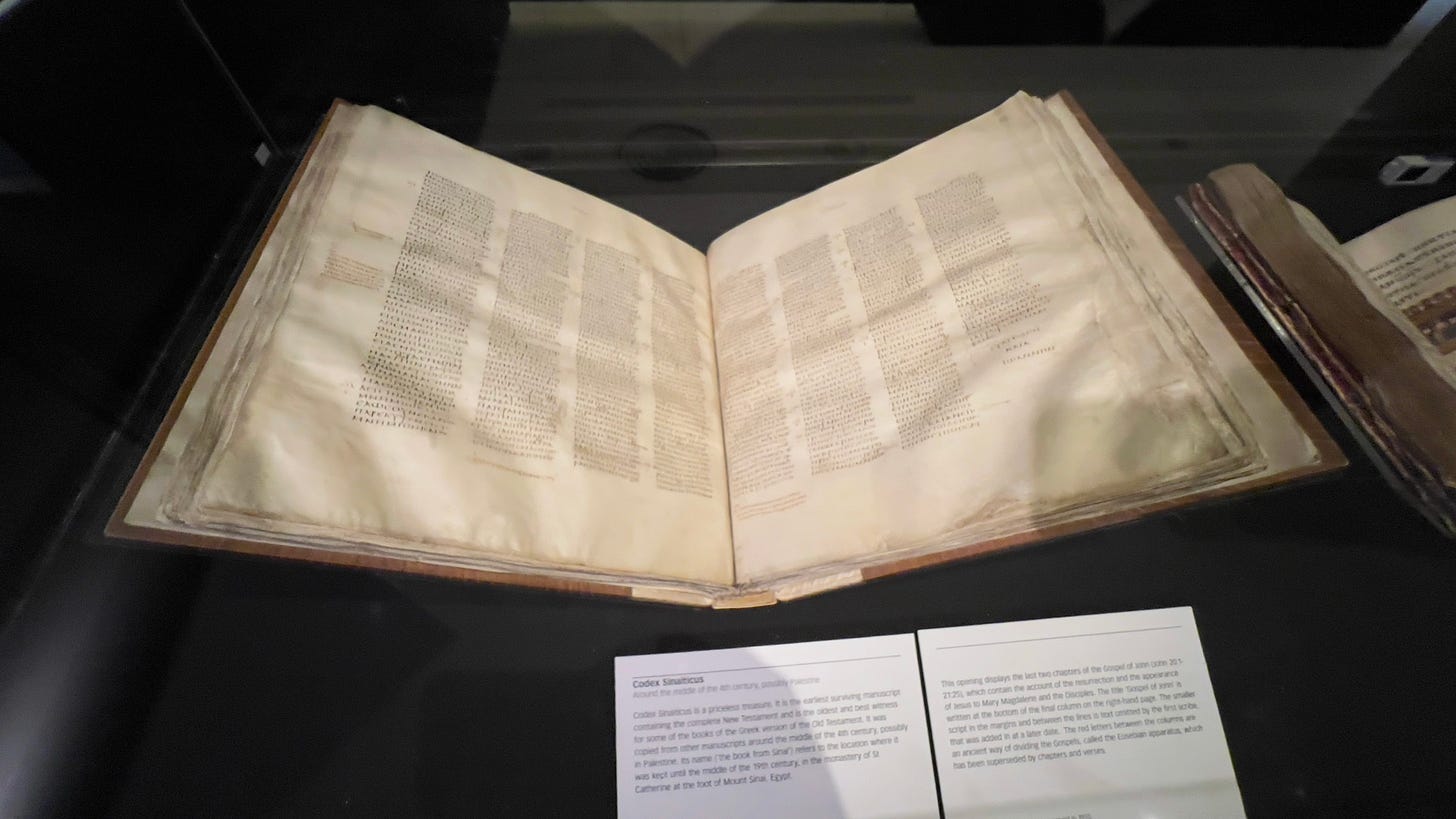

The apex of the design of the codex is considered to be the Codex Sinaiticus, seen below or view in person at the British Library. It’s three centuries into the codex development and refined to the point that from then on, no updates needed, never obsolete.

The codex is also credited with helping many ancient texts survive to the present day, the binding, cover method, and the durability of parchment has lasted many more centuries than papyrus.2

There’s so much that can be said about this incredible object. While reading has started to take on more forms throughout the years through kindles and audiobooks, it’s always the codex we keep coming back to again and again. In an era of rapid change and planned obsolescence, there’s something comforting about picking up a book—whether it’s 100 years old or fresh off the press—and knowing that it and the story therein is and will always be eternal.

Recommended Reading

The Medieval Scriptorium: Making Books in the Middle Ages by Sara J. Charles

The Birth of the Codex by C.H. Roberts & T.C. Skeat

Papyrus: The Invention of Books in the Ancient World by Irene Vallejo

The Bookmakers: A History of the Book in Eighteen Lives by Adam Smyth

The Book - The Story of Printing & Bookmaking by Douglas C. McMurtrie

Charles. Sara J. “The Beginnings.” The Medieval Scriptorium, Reaktion Books, 2024, pp. 34–35.

Roberts, C. H., and T. C. Skeat. “Epilogue.” The Birth of the Codex, Oxford University Press, 1982, pp. 75–76.